With an area of 2,729 km², Whiteshell Provincial Park is characterized by numerous lakes, rivers and the rugged Precambrian Shield. Forested areas are typically boreal forest of black spruce, white spruce and balsam fir, intermixed with trembling aspen, balsam poplar, and poorly drained tamarack or black spruce fens and bogs.

Classified as a Natural Park, its purpose is to preserve areas that are representative of the Lake of the Woods portion of the Manitoba Lowlands Natural Region and provide a diversity of recreational opportunities and resource uses. The park will:

- Provide nature-oriented recreational opportunities such as hiking, canoeing, mountain biking, snowmobiling and cross-country skiing that depend on a pristine or a largely undisturbed environment;

- Provide high-quality cottaging, camping, boating and angling opportunities, and accommodate related commercial developments, services and facilities such as lodges, trails, campgrounds, day-use areas and picnic sites;

- Protect and profile historical, cultural and archaeological sites;

- Promote public appreciation and understanding of the park’s natural features; and

- Accommodate commercial resource uses such as forestry, mining and wild rice harvesting where such activities do not compromise other purposes.

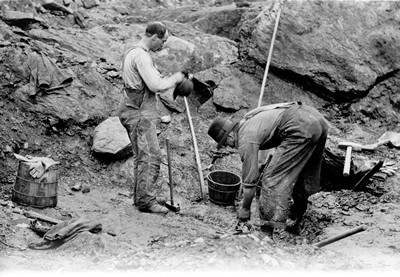

The Earliest Times From archaeological excavations along the Winnipeg River, human presence in the Whiteshell area has been traced back to at least 8,000 years ago. The different styles of projectile points, scrapers, hammerstones and ceramics indicate that the sites were periodically occupied by various cultural groups. Some of the artifacts found in the area are in the museum at Nutimik Lake.

Although the artifacts differ in style, it is clear that they had similar uses. The earliest inhabitants, and those who succeeded them, lived by hunting, fishing and gathering wild plants. For most of the year they moved from place to place in small family groups in search of game. Several times a year the families would gather to harvest resources and to conduct religious ceremonies.

The rock alignments (petro forms), which were built on the bedrock in various locations throughout the Whiteshell, have been attributed to Algonkian-speaking people, of whom the present-day Anishinabe (Ojibwe) are descendants. While the builders and the first people to use the petro forms have not been identified, these stones are not just relics of past rituals of unknown people. Their importance to Anishinabe continues to this day. The petro form sites are places where spirits teach those who are open to instruction.

Petroforms are arranged in the forms of snakes, turtles, humans and as geometric shapes. According to tradition these alignments were used in times past as sources of spiritual healing power by such societies as the Midewiwin, the Grand Medicine Society of the Anishinabe.

Members of the Midewiwin practice a code of ethics that promotes a long and healthy life through a commitment to the values of wisdom, love, respect, courage, honesty, humility and truth. The membership provides spiritual, physical and emotional healing to all who come to seek help. Increased knowledge in the use of natural medicines and in the power to heal are recognized by the member’s passage through four to eight stages or “degrees.” Advancement from one degree to another involves intensive periods of instruction, quests for spiritual knowledge, and initiation rights. The details of these rituals were often recorded in picture form on birchbark scrolls.

The name Whiteshell appears to be related to the small, white, sacred seashell known as the megis. Some Aboriginal people believe that it was through this shell that the Creator breathed life into the first human. To them, megis shells are symbolic of both the Creation and of the path of life as set out for the Anishinabe by the Creator. They are used by Midewiwin members in healing and initiation ceremonies. Today, some Anishinabe wear the megis shell as a reminder of the origin and history of their people.

If in your travels you come across a feature that you think might be a petroform, we urge you to leave it untouched and to report it to a Natural Resource Officer. In this way, you can participate in the recording and preservation of these testimonials to Manitoba’s rich Aboriginal heritage.

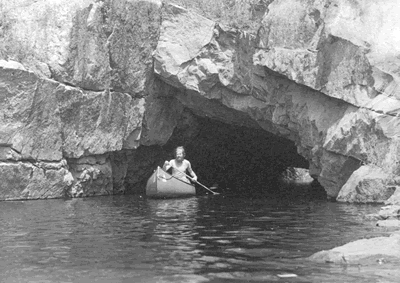

The Canoe Era When members of the La Vérendrye expedition arrived here in the spring of 1733, they found a Cree settlement at La Barrière. The Cree had built a weir to trap spawning sturgeon near the site of what is today the Opapiskaw campground. (The Whiteshell River, known as la rivière Pichikoka, was used by the La Vérendryes as an alternative route.) The French fur traders’ and explorers’ journey down the Winnipeg River was an important event in the development of the West. Prior to 1733 all explorations of Manitoba were along rivers that flow into Hudson Bay. Around 1800, the Cree moved to the north and west and the Anishinabe moved here from the vicinity of Lake Superior.

The Winnipeg River became an important fur trade route for the Montreal-based North West Company. Each spring, brigades of voyageurs took bundles of furs from inland posts to Fort William and returned with trade goods in late summer. These trips ceased when the North West Company and the Hudson’s Bay Company merged in 1821.

Alexander MacKenzie, David Thompson, Paul Kane, both Alexander Henry the Elder and the Younger were some of those who came west via the Winnipeg River.

What may be termed the canoe era in western Canadian history came to an end around 1870. The last major use of canoes was when Colonel Wolseley’s troops used them on their western journey to suppress the Riel Resistance.

La Vérendrye’s expeditions and fur trade history are major episodes of history throughout the Whiteshell and are promoted by the La Vérendrye Trail-a heritage route through Manitoba’s eastern region.

Railways and Roads A new era began with the development of the railway. In 1877 work began on two sections of what became the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR). This included the part through the Whiteshell, the last stretch on the Precambrian Shield before it tapers into the first prairie level. The line between Winnipeg and Fort William was fully operational by 1883.

The town of Rennie, named after a noted British engineer, was established as a coal-and-water stop for the steam locomotives which were used until the late 1950s. Now Rennie is the location for the headquarters of Whiteshell Provincial Park.

A second line, which was to become the Canadian National Railway, was built through the Whiteshell about 25 years after the CPR was completed. During construction of both railroads similar difficulties were encountered at Cross Lake. The swamp-lined lake seemed to be bottomless, and vast amounts of fill had to be used to build up the grades. Tunnels were blasted through solid rock during construction of both railroads to permit the easy flow of water. When water levels are high it is necessary to portage across the tracks.

The discovery of gold near Keewatin at the turn of the century sparked a great deal of activity in the Whiteshell. Some prospectors took the CPR train to Ingolf and set out by canoe expecting to strike it rich. Some of Manitoba’s earliest mineral claims were staked in the Falcon, Star and West Hawk Lake areas.

In the early part of the century there was an attempt to start farming in the Whiteshell and several 1/4-section homesteads were granted in the area. Most of the land, however, proved to be unsuitable for agriculture.

About 1920 the Whiteshell’s recreational potential began to be recognized. Three areas in particular drew public attention because they were adjacent or close to the railways. They were the Brereton Lake area, the Nora and Florence Lake area, and the West Hawk and Falcon Lake area. The first summer cottages in the Whiteshell were built in these places. Jurisdiction over the province’s natural resources was transferred from the Dominion of Canada to Manitoba in 1930, and in 1931 the province established the Whiteshell Forest Reserve. Work continued on a road through Whitemouth, Rennie, and past West Hawk Lake to the Ontario border. What is now Provincial Trunk Highway 44 served as part of the Trans-Canada Highway until the present route was completed in the mid-1950s.

Road construction took place as part of the Single Men’s Relief Program established to provide employment during the Depression years. About 1937 another road was built north from Rennie past Brereton, Red Rock, Jessica and White lakes to Big Whiteshell Lake. A few campgrounds, cooking shelters and picnic sites were established in conjunction with the roads to provide recreational opportunities.

Another important purpose of the roads in the Whiteshell was forest fire protection. Before the existence of roads, fire fighting crews were transported by airplane, canoe or train. However, each mode had its drawbacks. Airplanes had limited capacity, canoes were too slow and the railways provided access only to a small part of the forest reserve. Roads considerably reduced the time taken by crews to arrive at a reported fire.

Prior to 1930, fire patrols consisted mainly of reconnaissance flights by the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) at Lac du Bonnet. These were supplemented by canoe patrols and spotters at various locations. Communication was a major problem. There were no telephone lines in the forest reserve and no efficient radio communication between the aircraft and the base. Pilots, spotters, and patrolmen relied on homing pigeons to relay information on the nature and location of fires. When the resources were transferred to the province, the RCAF provided six Vickers-Vedette flying boats, two Lynx engines, spare parts and a breeding stock of homing pigeons. This marked the beginning of the Manitoba Government Air Service.

The system of fire protection in the Whiteshell improved greatly in the following years. Lookout towers were built in strategic locations throughout the forest reserve. As well, the government established telephone communication. Today, both towers and airplanes are equipped with efficient radios for quick and accurate reporting. Although helicopters and waterbombers and water pumps have been added to the equipment, the basic front-line tools of fire fighting have remained the same-axes, shovels and backpumps.

Today the backbone of fire detection in the province is the provincial lightning locator and positioning system. This computerized network of towers accurately pinpoints lightning strikes on a computer screen as the storm occurs. Once lightning strikes are plotted, aircraft patrol the affected area to locate the fires as soon as possible. Modern radio and communication equipment ensure that the fire boss is in communication with others on the ground as well as essential personnel in the aircraft above. All helicopters and waterbombers are equipped with global positioning systems (GPS) which allows them to locate or return to even the smallest fire in the wilderness.

The modern fire fighter depends upon the fast and efficient delivery of water via small portable gas powered water pumps and specialized aircraft like helicopters and Canadair CL-215 waterbombers.

In 1961, the Whiteshell was designated a provincial park, as part of a system of lands set aside for the benefit of both Manitobans and visitors.

If you spot a fire, please report it by calling 1-800-782-0076.

After Summer The holiday weekend in September signals the end of summer. The departure of most vacationers is soon followed by the changing of leaves on deciduous trees and tamarack. The spectacle of fall colours can be observed from the park’s roads. Mushrooms thrive among the newly fallen leaves.

Autumn is the time for a long-standing activity in the Whiteshell-the wild rice harvest. Stands of rice fill the bays of some lakes and crowd the banks of the Whiteshell River in places. The rice is harvested in traditional fashion. One person poles a canoe through the rice field while another bends the stalks into the canoe and knocks the ripe grains off with a picking stick.

Early winter in Whiteshell is also beautiful. As temperatures drop in the late fall the heat loss from the water bodies creates eerie misty mornings. Hoarfrost coats the trees along the shore when the temperature falls below freezing. Migratory birds depart leaving behind grosbeaks, chickadees, ravens, whiskey-jacks and grouse.